Kimberley Howe: When I hear “art theft,” I always flash on the movie, The Thomas Crowne Affair. If you delve into Otho Eskin’s new novel, you’ll learn about a dazzling heist that still remains unsolved today—an event he uses as a springboard for a compelling story that brings big Pharma together with high-end thievery!

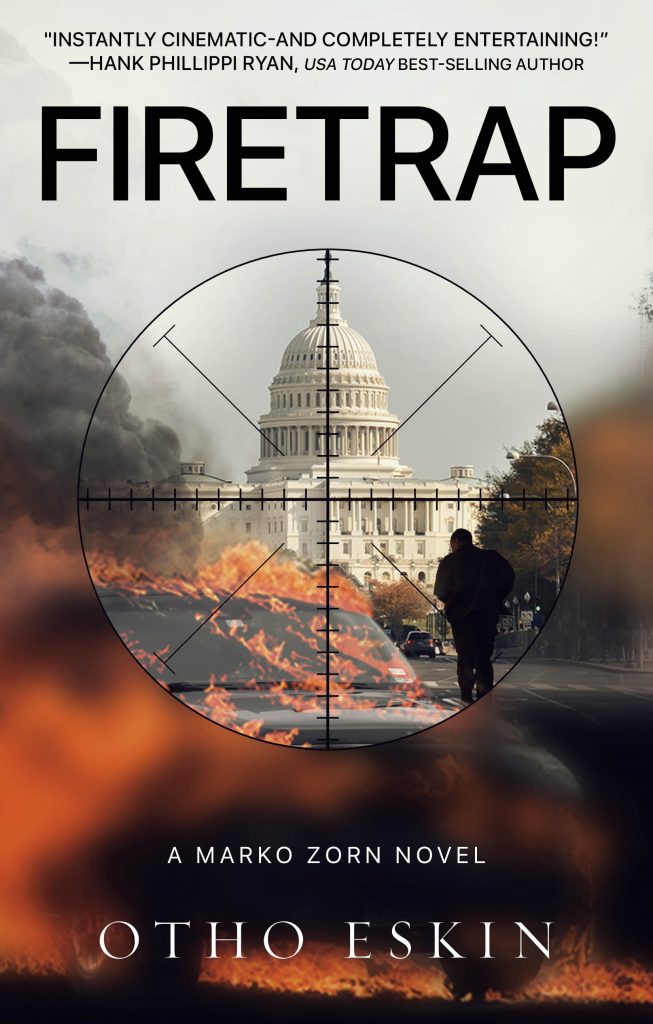

The Real-Life Art Heist that Inspired My Latest Thriller Firetrap

By Otho Eskin

Status: stolen, missing.

On the night of March 18, 1990, two men, dressed as Boston policemen, broke into the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. They handcuffed the museum guards and proceeded to steal thirteen paintings, including works by Rembrandt, Manet, and Vermeer. The entire robbery lasted only eighty-one minutes. The FBI estimates the value of the stolen art at $600 million.

Despite the Gardner Museum’s offer of $10 million for information leading to the recovery of the stolen art, the mystery of their theft remains unsolved and their location unknown. Today, empty frames hang in the galleries as placeholders and a dramatic reminder of what is deemed one of the highest-value museum robberies in history.

When I visit the Gardner Museum and see the empty frames, I wonder: Are the thieves still alive? What kind of people steal art they can’t sell through normal channels or even display? Do they have any remorse at all? Above all, what happened to the art?

These paintings were so famous and the theft so publicized that their sale, even on the large and lucrative black market for stolen art, would be very problematic. On occasion, insurance companies will pay ransoms if they are well below the art’s market value. I suspect that the majority of high-profile art theft is committed by robbers contracted by ultra-wealthy art collectors compelled to add the artwork to their clandestine collections. This is also the hypothetical scenario attributed to the Gardner Museum robbery and the basis for part of the plot in Firetrap, the third novel in my Marko Zorn series.

Firetrap takes D.C. homicide detective Zorn on his most dangerous mission yet. A street drug named Speedball, five times as potent as fentanyl, is spreading across the nation, and Zorn’s hunt for those responsible for the drug leads him to a Big Pharma corporation run by mysterious, psychopathic twin brothers. Zorn discovers that the brothers ordered the murder of a former employee and whistleblower, as well as a scientist at the Food and Drug Administration who was fighting to stop the company’s criminal activity.

Zorn learns that one of the twins, who is legally blind, is in possession of Vermeer’s The Concert, one of only thirty-six known paintings by Vermeer and one of the paintings taken from the Gardner Museum. Even though the blind twin clearly can’t fully appreciate the painting, he wants to possess it. This stolen painting provides the key that enables Zorn to cripple the vast criminal drug empire.

The Gardner Museum heist was seemingly not simply for financial gain; it was more complex and devious. I’m convinced the mastermind who planned and organized the theft was motivated by a pathological desire to acquire a work of art for the sole purpose of denying it to the rest of the world.

This led me to consider the analogy to Big Pharma, wherein certain companies manipulate the medical profession and the market, and deceive regulators and members of the public through predatory and deceptive marketing and price gouging. They do this not just for profit, but because they can.

I was inevitably thinking of the Sackler family, once the owners of Purdue Pharma, the company that produced and sold the drug OxyContin, responsible for an epidemic of addiction and thousands of deaths.

Arthur, Raymond, and Mortimer Sackler were the children of immigrants from Eastern Europe. All earned medical degrees and, in 1952, the brothers bought Purdue Frederick, then a small pharmaceutical company. Raymond and Mortimer ran the company while Arthur concentrated on marketing to doctors. Collectively, these men built what now goes by Purdue Pharma into a formidable moneymaking machine. After Arthur died of a heart attack in 1987, his share of the company was sold to Raymond and Mortimer, who went on to develop and sell Oxycontin in 1996. They pursued now-infamous Machiavellian promotional tactics that led to astronomical sales and earned the family billions. After the brothers’ deaths, Mortimer in 2010 and Raymond in 2017, their children took over Purdue’s management.

Of course, the Sackler family is also famous for their generous donations to universities and museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Louvre in Paris, and the Tate Modern in London. Starting in 2018, photographer Nan Goldin led a relentless campaign against the Sacklers, galvanizing other artists to join her highly publicized protests outside museums. The following year, the Louvre removed the Sackler name from its galleries. The Metropolitan Museum followed suit in 2021 and the Tate Modern, in 2022.

Arthur Sackler’s daughter, Elizabeth A. Sackler, who along with her mother, received no profits from the sale of Oxycontin, called Purdue’s actions “abhorrent.” It has since been revealed that her relatives withdrew billions of dollars from the company before filing for bankruptcy in 2019.

But the actions of Purdue’s owners and representatives are a symptom of a larger more pernicious problem: the madness of America’s public healthcare system, which enables drug manufacturers to pursue obscene profits, regardless of the cost to society.

Many Americans have lost friends or family members to opioid abuse. They will never recover their loved ones, the death toll continues to climb, and recent legal proceedings in Purdue Pharma’s bankruptcy proceedings have stalled financial restitution.

One of the virtues of fiction is that it allows people to imagine justice triumphing in the end. Stories tell us that, while there are indeed bad people, there are also good people like the whistleblower and the FDA scientist in my novel, Firetrap. These are the men and women who work to combat crime and corruption and bring evil-doers to account and ensure that public goods—including art and life-saving medicine—benefit the right people. Firetrap is dedicated to them.

What are your theories on what happened to the stolen art works?

Otho Eskin is a lawyer and a former member of the United States Foreign Service. He has served in Washington, Syria, Yugoslavia, Iceland, and Berlin (then the capital of the German Democratic Republic) as a lawyer and diplomat. He was Vice-Chairman of the U.S. delegation to the United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea and represented the United States in negotiations at several other UN Committees. He was a frequent speaker at conferences and has testified before the U.S. Congress and commissions. He speaks French, German, and Serbo-Croatian. In his retirement, he is active in the Washington theater scene and a playwright whose work has appeared in New York, Washington, D.C., and Europe. Firetrap is his third novel in the Marko Zorn Thriller Series, following The Reflecting Pool and Head Shot. He lives with his wife, Therese, in Washington, D.C.

0 Comments